Many consumer surveys point to an obvious conclusion: most people hate seeing ads on smartphones and tablets. But the truth is, contrary to the desire for an ad-free experience, when faced with the choice between free apps with ads, or paying even $.99 for apps without ads, consumers overwhelmingly choose the free apps and tolerate the ads.

In this post we explore that revealed preference for free content over content free of ads by examining four years worth of pricing information for the nearly 350,000 apps that use Flurry Analytics.

Each time we download an app, we reveal a little bit about ourselves. A glance at the apps on your phone can indicate whether you are a fan of sports, gaming, or public radio, and whether you love to hike or cook or travel. But our choices of apps also reveal our individual tolerance for advertising, and how we feel about the trade-off between paying for content directly, or paying indirectly by (implicitly) agreeing to view ads.

In many cases, apps are available in two forms: free (with ads) and paid (no ads). If you truly can’t stand to see ads in apps, you can usually pay $.99 or $1.99 to eliminate the ads and possibly get some additional functionality too. Even when a specific app does not come in paid and free versions, there are often other apps to choose from, free and paid, that perform very similar tasks like calling a taxi or looking up recipes.

So what are consumers choosing? Let’s start by considering iOS apps since they have been available for longer than Android apps. Note that all of our measurements in this post are weighted by user numbers so the apps with more users contribute more to the total trend.

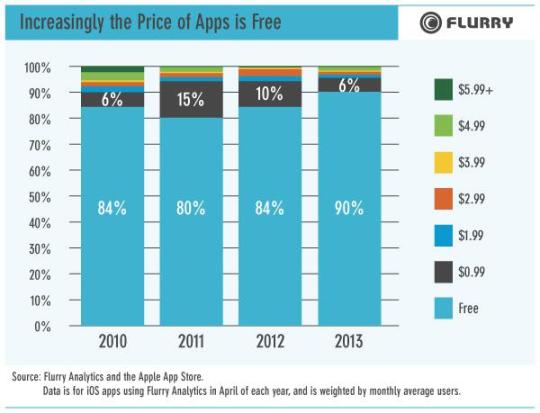

The chart below shows how the proportion of free versus paid apps has changed over the years in the App Store. Between 2010 and 2012 the percentage of apps using Flurry Analytics that were free varied between 80% and 84%, but by 2013, 90% of apps in use were free.

Some might argue that this supports the idea that “content wants to be free”. We don’t see it quite that way. Instead, we simply see this as the outcome of consumer choice: people want free content more than they want to avoid ads or to have the absolute highest quality content possible. This is a collective choice that could have played out differently and could still in particular contexts (e.g., enterprise apps or highly specialized apps such as those tracking medical or financial information).

Up until now, we have focused on iOS apps because they have been around longer, but what about Android? Conventional wisdom (backed by a variety of non-Flurry surveys) is that Android users tend to be less affluent and less willing to pay for things than iOS users. Does the app pricing data support that theory? Resoundingly.

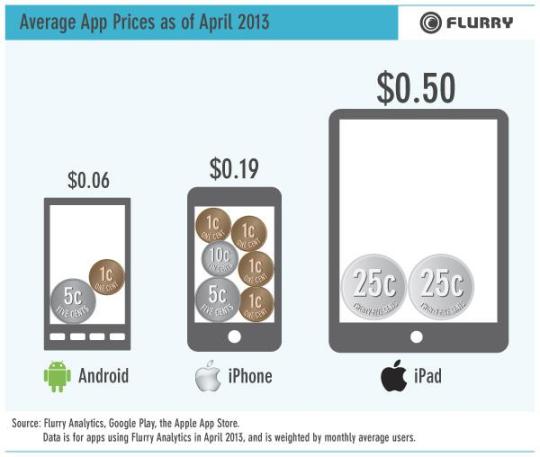

As of April 2013, the average price paid for Android apps (including those where the price was free) was significantly less than for iPhone and iPad apps as shown below. This suggests that Android owners want app content to be free even more than iOS device users, implying that Android users are more tolerant of in-app advertising to subsidize the cost of developing apps.

These results also support another belief derived from surveys and some transaction data: iPad users tend to be bigger spenders than owners of other devices, including iPhone. On average, the price of iPad apps in use in April of this year was more than 2.5 times that of iPhone apps and more than 8 times that of Android apps. This is likely to be at least partly attributable to the fact that on average iPad owners have higher incomes than owners of other devices.

On the surface, the rise of free apps could be seen as herding behavior: maybe app developers saw how much free competition there was and decided to make their apps free too. It’s certainly possible that may have happened in some instances, but by digging deeper into app pricing patterns over time, we were able to see that many developers took a much more thoughtful approach to pricing.

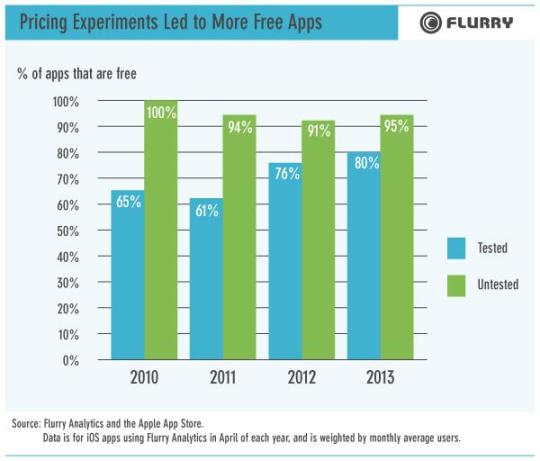

We looked at historical iOS app data (again because iOS apps have a longer history) to identify apps that have been the subjects of pricing experiments. That typically took the form of A/B testing, where an app was one price for a period of time then the price was raised or lowered for a period of time, then raised or lowered again. This lets developers assess users’ willingness to pay (i.e., price elasticity of demand) based on the number of downloads at different price points.

The chart below shows the percentage of tested and untested apps that were free (again, weighted by user numbers). The vast majority of untested apps in green were free all along, so it’s most interesting to look at the trend among apps that were subject to pricing experiments, in blue. As shown, there was an upward trend in the proportion of price-tested apps that went from paid to free. This implies that many of the developers who ran pricing experiments concluded that charging even $.99 significantly reduced demand for their apps.

While consumers may not like in-app advertising, their behavior makes it clear that they are willing to accept it in exchange for free content, just as we have in radio, TV and online for decades. In light of that, it seems that the conversation about whether apps should have ads is largely over. Developers of some specialized apps may be able to monetize through paid downloads, and game apps sometimes generate significant revenue through in-app purchases, but since consumers are unwilling to pay for most apps, and most app developers need to make money somehow, it seems clear that ads in apps are a sure thing for the foreseeable future. Given that, we believe it’s time to shift the conversation away from whether there should be ads in apps at all, and instead determine how to make ads in apps as interesting and relevant as possible for consumers, and as efficient and effective as possible for advertisers and developers.